This post was written by Hannah Wang, Senior Digital Preservation Specialist.

The NARA Digital Preservation Unit is very excited to announce that the most recent release of the Digital Preservation Framework is now available on GitHub. This release includes a major overhaul of the Risk Matrix, with new and updated questions about how we evaluate risk to file formats, as well as a new report on the file format extensions present in our holdings.

This blog post is the third in a four-part series about this major re-release, where I’ll talk about our process for revising the Risk Matrix. In the first post, I introduced the Framework, and in the second post, I discussed what exactly has changed in this new release. The final post will discuss some interesting findings and takeaways from this whole process.

We were lucky to work with the Public Affairs team at NARA to put together this article about the updates to the Framework; it’s a great high-level overview of this project and digital preservation at NARA. And if you want even more information about how we assess file format risk at NARA, you can check out our paper, co-written with our Library of Congress colleagues, that we presented at the International Conference on Digital Preservation in September.

Why did we update the Risk Matrix?

When I joined NARA in 2023, the Risk Matrix had grown to over 700 file formats over four years. The questions in the Risk Matrix had been applied to a large variety of formats, and it was time to assess it as an instrument for performing these risk assessments.

Initially, we wanted to revise the Risk Matrix because of inconsistently applied scoring logic. As I discussed in the last post, there were implicit logic pathways between questions that were inconsistently followed. This meant that two similar formats could be scored very differently depending on how the scorer interpreted the logic in the questions.

So we put a task on our work plan for FY 2024 to “Map out scoring logic for the risk matrix to standardize risk factor scoring.” As we started to examine the questions themselves, this quickly ballooned into a much larger nine-month project and major overhaul of the Risk Matrix.

What was our process?

Iteration and (necessary) scope creep

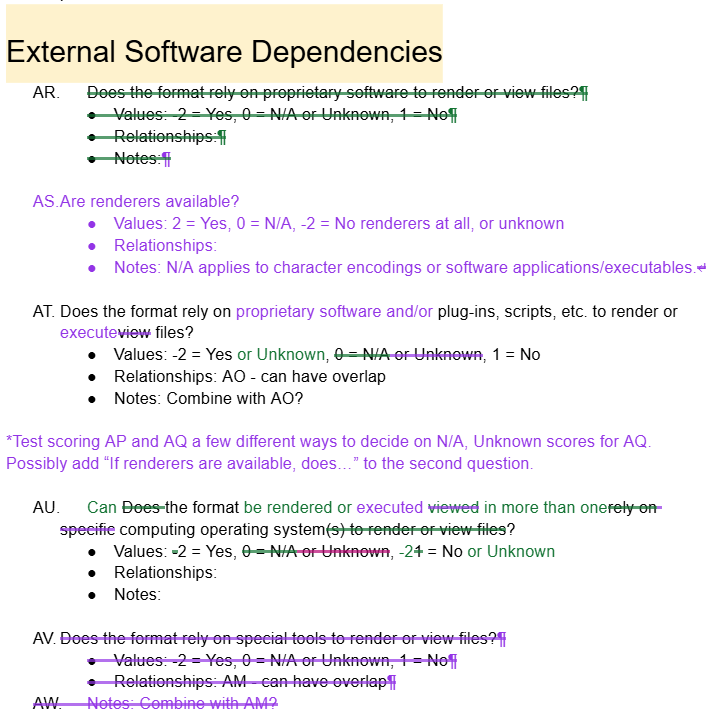

In January 2024, Elizabeth convened a series of meetings for the Digital Preservation Unit (then Elizabeth, myself, and Leslie Johnston, Director of Digital Preservation) to talk through each of the sections in the Risk Matrix. Although we started with examining the scoring logic, we also wanted to make sure that we made any other critical updates at the same time, so that we didn’t have to do this kind of revision too often.

As we started to pick apart the questions, we discovered many other changes that we wanted to make, based on our experiences of scoring formats in the Risk Matrix, including:

- Merging similar questions to make scoring easier

- Adjusting scores for questions that seemed more/less important

- Rephrasing or removing questions that were too vague or difficult to answer for formats across all categories

The Google Doc soon looked like this:

We also brought in subject matter experts from custodial and policy-making units at NARA to weigh in on some of the questions.

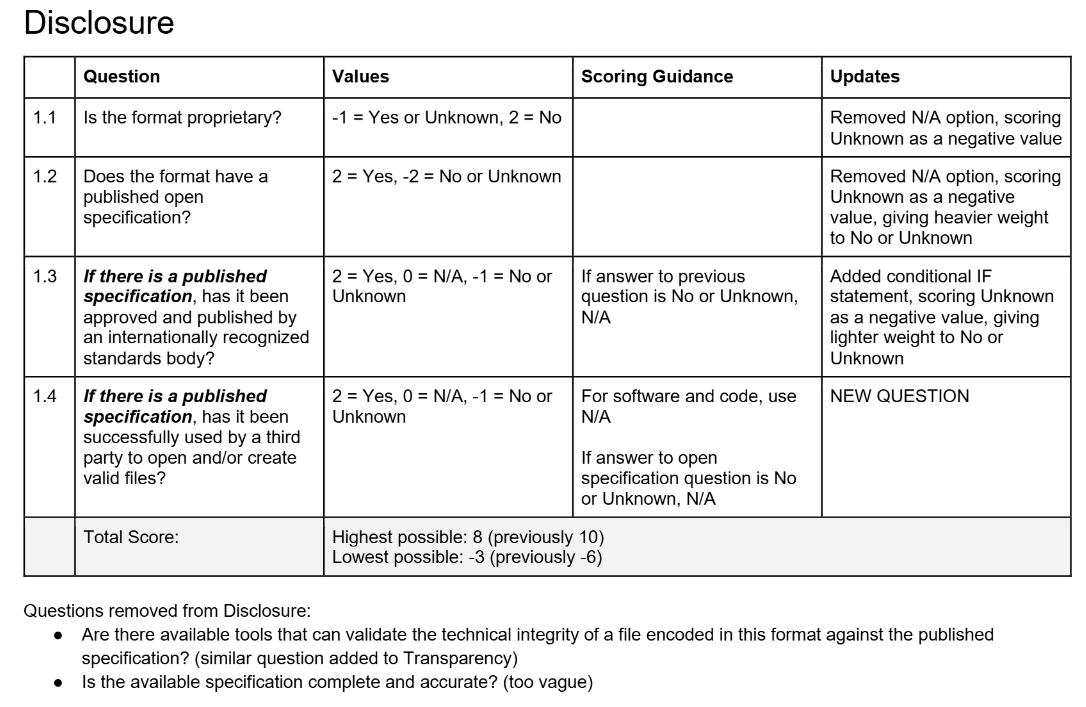

After we finished making this first round of proposed changes, we created an updated version of the Risk Matrix spreadsheet and scored a 10% sample (72 formats), covering all categories of formats. This test sample revealed some areas where we needed to refine the questions (iteration is going to be a theme here), so we made another round of updates before summarizing them into a list of proposed updates.

Community feedback

We published these proposed updates on GitHub and sought feedback from both colleagues at NARA and members of the international digital preservation community. We received detailed feedback from colleagues at six other organizations. This feedback was a vital part of the process, because it brought in perspectives from people who think a lot about file formats and resulted in some of the most impactful changes to the Risk Matrix.

Some of the feedback raised valid technical points that we had considered but were unsure how to articulate, such as the relative importance of open-source renderer availability and a format’s ability to support declared or hidden embedded data. We added some additional questions to address those factors.

There were also some common points of confusion about terminology that we used in the Risk Matrix (e.g., what do we mean by “robust” encryption?) that we tried to address through clearer language and defining our terms.

There was also some feedback along the lines of, “Why do you care about the answer to this question?” To address this, we decided to write justification statements for each question, which you can now find in the readme file for the Risk Matrix. This kind of feedback was also a factor in creating the blog you’re currently reading: we realized that it was important to write more about the context of our risk assessments as well as other digital preservation work at NARA. We’re excited to share more about the work we do!

After this final iteration over the questions in the Risk Matrix, we set up a new spreadsheet to rescore all 729 file formats. This is also the point where I created the new dual view of the Risk Matrix: there is now one spreadsheet with the “human-readable” version with Yes/No/Unknown/N/A responses to each question (where we input all the information), and one spreadsheet with the corresponding numeric values used to calculate the Risk Rating. You can read more about this in the last post.

Rescoring

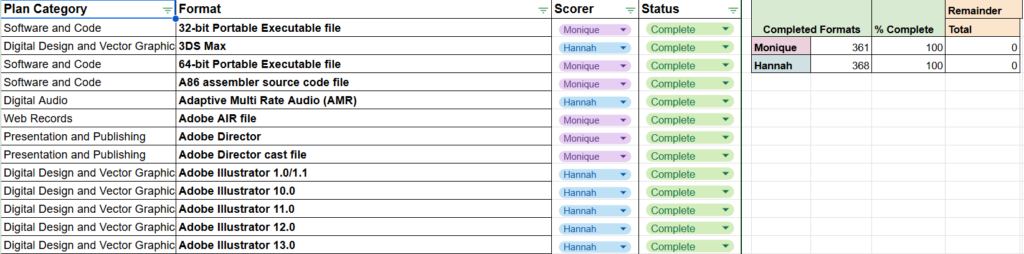

Our Senior Digital Preservation Analyst, Monique Lassere, and I went to work on rescoring these 729 formats. We divided the work in half, updating our progress in a tracking spreadsheet, which helped to slightly “gamify” the process.

I won’t lie – the next three months were a bit of a slog! With the new questions (and questions that were similar but just slightly different), we had to basically start from scratch researching and rescoring each of the formats that had been added over a period of four years. The process of researching and performing a risk assessment for a file format takes quite a bit of time (maybe we’ll write about that at some point). On the other hand, this kind of heads-down work can also be extremely satisfying and meditative!

We performed a peer review on a 10% sample for each category (e.g., digital audio, geospatial). At the end of each month, we would exchange a list of formats that we had rescored that month and wanted the other to review. This was a really helpful new element in this process, because it made me think more about making defensible decisions – we may want to incorporate more peer review into our Framework processes going forward.

Since we divided up the work by format category, we were able to think more about how to standardize the question scoring within each category for the first time. For example, questions about rendering would be answered differently for formats in the Software and Code category than for formats in the Digital Still Image category. We made notes about these considerations to include in our internal documentation and scoring guidance.

Finalization and publication

At the beginning of September 2024, we were finally done with rescoring! We adjusted the thresholds for Risk Levels; as a general guideline, we deem the lowest-scoring 10% of formats to be High Risk, the highest-scoring 25% of formats to be Low Risk, and the rest in the middle to be Moderate Risk. Because we had made so many changes to the questions and relative weights of different risk factors, we needed to wait until we had rescored all formats to update these thresholds accordingly.

Then we moved into quality control and finalization mode. We made sure that scoring logic had been applied consistently across all questions, that there were no cells with null values, and that all of the formulas were written correctly. We also looked at all the file formats that changed Risk Levels or had drastic changes in Risk Rating to make sure that these major changes were the result of new questions/logic and not scoring errors (I’ll be taking a closer look at these formats in the next post).

Finally, we published everything on GitHub and archives.gov. In addition to our usual updates to the spreadsheets, changelog, and linked open data, we published new documentation about this project (including the justification statements for each question that I discussed above). Then we were done! We shared some celebratory GIFs and emojis.

In the final post, I’ll conclude by sharing some of our major findings and takeaways from this process. See you then!